Meet real-life Indonesian Robinson Crusoes

BBC

Despite living in utter isolation on a desert island for 40 years, one inspirational couple has overcome disability and blindness to make a difference.

For a man who’s spent more than 40 years on a deserted island, Daeng Abu fizzes with a surprisingly exuberant love of life.

As he welcomed us to Pulau Cengkeh (Clove Island), a white-sand islet off the coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia, Abu’s toothless gums gaped in a joyous cackle. His blind, white eyes disappeared in ripples of laughter lines and his leprous hands reached out in a warm embrace. He and his wife Daeng Maida have lived alone on Pulau Cengkeh since 1972.

Neither knows how old they were when they entered their arranged marriage on nearby Pulau Pala (Nutmeg Island) – they currently believe they’re in their 80s – but Abu thinks he was older than 20 and Maida remembers it was the dry season. Her uncle fired three shots in the air; she walked over to his family’s home; Abu built a shack from bamboo and palm leaf; and married life began.

Little did they know at the time – the couple was bound to become a rather unlikely pair of environmental activists, spending their days raising sea turtles and speaking against the cyanide and dynamite fishing that is devastating Indonesia’s reef. But first, life had other plans.

As the couple settled into marriage, Abu free-dove to depths of 25m or more for giant clams and abalone, embarking on weeklong fishing trips around the islands. Maida kept their house, cooked and wove. Wet season turned to dry season, and dry to wet. Sometimes they ate fish, sometimes only rice. And Maida bore six children; five died of shaking sickness before the age of one.

Sakká, their only surviving child, was already grown when Abu realised something was terribly wrong. “I was diving for abalone,” he recalled. “I felt my body was getting bigger, that it was packed tight like a sack of cement.”

In the dark of night, Abu set out for the city, Makassar, paddling and sailing for 12 long hours. Many times, over many years, he made this journey. The family always prioritised medicine over food.

While speaking with me, Abu scraped his long, black thumbnail down his forearm, then again across a thigh, recalling the day the “big doctor” tested him for feeling and found he’d lost sensation in his limbs. When Abu told Maida he had kusta, the local term for leprosy, she wept. If Abu couldn’t dive, or at least catch fish, the couple would not eat.

Soon after, in 1972, the head of their district asked for volunteers to live and raise turtles on Cengkeh, about an hour by sailboat from Pala. Nobody wanted to go. But Abu felt a desert island would be the perfect spot to escape both social stigma and the risk of infecting others as his disease followed its disfiguring course. A turtle hatchery was work the pair of them could do, and the government stipend would keep them when he became too sick to fish.

He disassembled their house, loaded it and their few possessions onto a boat and sailed it to Cengkeh. “Everyone was crying,” he recalled. “They were saying: ‘Why are you going to the island? It’s like you’re a bad guy.’”

And, alone on Cengkeh that first evening, as the sun set, they cried, too.

Many Buginese islanders bury their dead on uninhabited islands for fear of ghosts and walking corpses. Cengkeh was once one of these islands of the dead, and even today the pair still say they hear the spirits and feel their grasping hands.

But when they arrived, Cengkeh was just a barren teardrop of sand, offering no shelter from blazing sun or bitter storms. Abu planted seeds, which grew into shady trees enmeshed with tangled vines, and generation after generation of baby turtles emerged, flippers flailing, from their nests in the soft sand.

In the early days, the pair raised them for sale in Makassar, perhaps for aquariums, more likely for meat. But as government priorities changed, so did their role, and now they raise turtles for release.

Indonesia’s 17,000-or-so islands sprawl over 5,000km across the equator amid one of the world’s most biodiverse and extensive coral reefs – more than 80% of it under threat. Turtles are essential to this fragile ecosystem: by feeding on destructive algae and sponges, they keep the coral healthy.

Yet there’s a larger threat to the coral than turtle loss. Cyanide and dynamite fishing emerged in the 1990s as a labour-saving technology that helped local fishermen catch fish for export. By throwing a handful of pesticide or a water-bottle bomb onto the reef, a bounty that might have taken weeks to catch would float to the surface as if by magic.

Abu – who believes he is now cured of leprosy – is a voice of age and wisdom in this cluster of islands. Cengkeh is much less isolated than is used to be, and Abu teaches passing fishermen and visiting islanders that killing coral kills the catch. Sometimes he reports “fish bombers” to the police; more often he enlists friends or family members to talk to them.

In an area where literacy levels are low and some islands have already annihilated their fringing reef, this micro-activism is vital: his message spreads from islet to islet, and even to the mainland. And Cengkeh’s reef remains as pristine as it was when he first started diving more than 60 years ago.

Life can be hard on Cengkeh: a few years ago, the couple almost died of thirst after a delivery of fresh water did not arrive. Yet Abu’s sightless eyes glistened as he remembered the reef. “It’s unbelievably wonderful and perfect,” he enthused. “There’s black, blue, yellow, green, red…. so many colours!”

I watched their loving, patient teamwork, the steady routine of a long marriage, as Maida guided her husband down the well-trodden paths to their solid wooden house. An Indonesian NGO, Dompet Dhuafa, built it for them a few years ago in honour of Abu’s environmental work.

The wind was getting up and the mirror-flat sea was starting to chop. It was almost time to leave.

“I would change nothing about what God has given me,” Abu emphasised. “I’m happy. It’s very peaceful. Everything – even disease, is a gift from God.”

Practicalities

To visit Cengkeh, take a taxi from the town of Pangkep, north of Makassar, to the port of Maccini Baji. From here you can catch a fishing boat to Cengkeh.

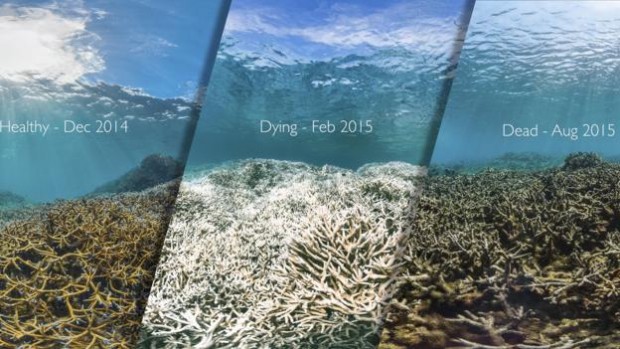

The effects of coral bleaching

The image above shows the same reef before, during and after a devastating coral bleaching event in American Samoa.

Like in Indonesia, coral reefs around the world face similar threats. As underwater ecosystems change and water temperatures increase, marine life deteriorates rapidly. “Coral bleaching”, for example, refers to the whitening – an indication of stress – and impending destruction of these fragile organisms.

How to submit an Op-Ed: Libyan Express accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. Submissions may be sent to oped@libyanexpress.com. Please include ‘Op-Ed’ in the subject line.

- Libya’s HCS invites applicants for key state roles - December 31, 2023

- UK calls on Iran to prevent escalation in Israel-Hamas conflict - November 05, 2023

- Libyan Interior Minister: Immigrant shelter costs a fortune - November 05, 2023