A fifth of world’s adults to be overweight by 2050, a study surmises

UK is on track to have the highest obesity levels in Europe, while a fifth of world’s obese adults live in six high-income English-speaking countries

About a fifth of all adults around the world and a third of those in the UK will be obese by 2025, with potentially disastrous consequences for their health, according to a study.

The research published by the Lancet medical journal says there is zero chance that the world can meet the target set by the UN for halting the climbing obesity rate by 2025.

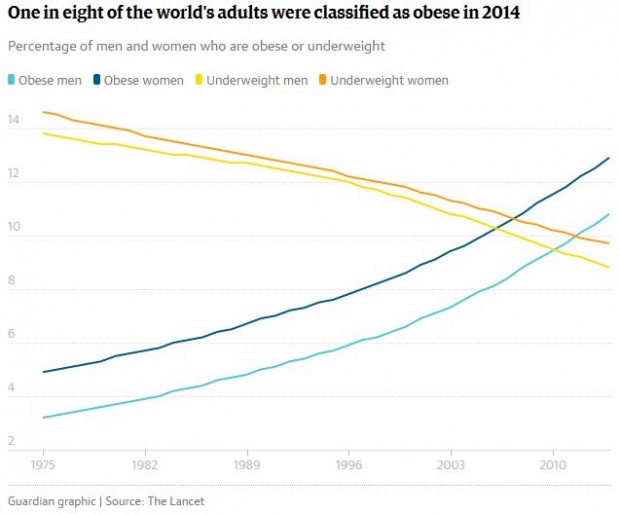

“Over the past 40 years, we have changed from a world in which underweight prevalence was more than double that of obesity, to one in which more people are obese than underweight,” said senior author Prof Majid Ezzati from the school of public health at Imperial College London.

“If present trends continue, not only will the world not meet the obesity target of halting the rise in the prevalence of obesity at its 2010 level by 2025, but more women will be severely obese than underweight by 2025.”

The English-speaking world is particularly badly affected. By 2025, the UK will have the highest obesity among both men and women in Europe, at 38%, say the researchers. Almost a fifth of the world’s obese adults (118 million) live in just six high-income English-speaking countries – Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK and the US. More than a quarter (50 million) of the world’s severely obese people also live in these countries.

Obesity is commonly measured by BMI (body mass index, which is body mass divided by the square of the body height) a measure which has well known flaws at an individual level, since muscular athletes may have a high BMI without being obese. But it is the best-used measure for over and underweight across whole populations.

People with a BMI below 18.5 are considered underweight while 35 or higher is considered severely obese and 40 or higher is morbidly obese. People with very high BMIs are considered to be at risk of heart disease, diabetes, cancer and other serious health problems.

Looking at studies on BMI across the world over the last 40 years, the researchers found a startling increase, they say, from 105 million obese people in 1975 to 641 million in 2014. The proportion of obese men has more than tripled since 1975 from 3.2% to 10.8% and in women, it has more than doubled, from 6.4% to 14.9%.

Against the trend of steadily rising weight, women in some countries had virtually no increase in BMI over the 40 years – in Singapore, Japan, and a few European countries including Czech Republic, Belgium, France, and Switzerland.

The highest average BMI rate in the world is in the islands of Polynesia and Micronesia, where they reach 34.8 for women and 32.2 for men in American Samoa. More than 38% of men and over half of women are obese in Polynesia and Micronesia.

Ezzati said much more needs to be done. “This epidemic of severe obesity is too extensive to be tackled with medications such as blood pressure-lowering drugs or diabetes treatments alone, or with a few extra bike lanes. We need coordinated global initiatives – such as looking at the price of healthy food compared to unhealthy food, or taxing high sugar and highly processed foods – to tackle this crisis.”

The lowest average BMI rates in the world are in Timor-Leste, Ethiopia, and Eritrea. Timor-Leste was the lowest at 20.8 for women and Ethiopia the lowest at 20.1 for men.

Concern over soaring obesity rates should not lead to the neglect of those who are underweight around the world, said Prof George Davey Smith from the integrative epidemiology unit, at the University of Bristol’s school of social and community medicine in a comment in the journal.

“A focus on obesity at the expense of recognition of the substantial remaining burden of undernutrition threatens to divert resources away from disorders that affect the poor to those that are more likely to affect the wealthier in low income countries.”

Prof Neena Modi, president of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, said the results were a stark reminder to the government of the work that remained to be done. “This is an international problem, and worldwide joined-up thinking is needed to make progress,” she said.

“The UK can be a world leader in tackling obesity and the government’s upcoming children’s obesity strategy provides a good opportunity to be that leader. The recent announcement of a sugar tax is a welcome start. We look forward to seeing a rigorous evaluation of its impact so that other countries can benefit from this excellent UK example.

“A number of additional measures are also required. More research to reduce childhood obesity risks that arise in the womb during pregnancy, and in infancy are essential. The more that is known about underlying causes, the better this worldwide crisis be addressed.”

How to submit an Op-Ed: Libyan Express accepts opinion articles on a wide range of topics. Submissions may be sent to oped@libyanexpress.com. Please include ‘Op-Ed’ in the subject line.

- Libya’s HCS invites applicants for key state roles - December 31, 2023

- UK calls on Iran to prevent escalation in Israel-Hamas conflict - November 05, 2023

- Libyan Interior Minister: Immigrant shelter costs a fortune - November 05, 2023